It was always something I did well but it wasn’t until I was 19 or 20 that I decided to try to make it my living

Writing was the one thing—the only thing—I excelled at in school. For some reason, I was an indifferent student and my marks showed it. But my marks in English composition during my last year in high school were in the top three percent in the province of Quebec. As author Dennis Lehane put it so memorably at one conference, “I became a writer because I sucked at everything else.”

This wasn’t entirely true in my case. I always had a good singing voice and in my teen years had my heart set on fronting a rock band. But experience proved I was good at it—not great—and in that business, good isn’t good enough.

The summer I was 19, I was out of school and working in a garment factory. One day, a sentence came into my head—”He walked with a step that belied his sixty years”—and wouldn’t leave until I wrote it down on the back of a pink telephone message slip. By the end of the day I had filled six or seven slips with notes and within a few weeks had completed my first story, a melodramatic tale of a young travelling musician who meets an older drifter who turns out to be (significant organ chord) his father. By the end of the summer, I had finished half a dozen stories and was on my way

Yes and yes.

Yes and yes.

I earned an Honours degree in creative writing and journalism at Concordia University in Montreal in 1979. The courses gave me an opportunity to have my work critiqued by teachers and students alike. Most of all, they gave me deadlines to meet. I was also fortunate to have some great teachers: Clark Blaise, one of the most talented writers of short fiction of his day; Gary Geddes, a poet with a keen eye for language; Terrence Byrnes, who instilled in me the need to treat every word with care; and Enn Raudsepp and Lindsay Crysler, who encouraged my efforts on the journalism side.

There is, however, a caveat. Classes alone will not make a writer of someone who lacks talent or drive. When I enrolled in journalism, I stopped in at the student newspaper, then called the Georgian, and asked if they needed writers. The editors practically barred the door so I couldn’t escape. I had my first assignment before I ever took a class and over the next two years published scores of articles and columns. The students who simply took their courses and did their homework did not establish writing careers. Those of us who worked at the paper, or the campus radio and TV stations, for the most part did find work in their chosen field.

The same was true on the creative writing side. In my first year, some 35 students enrolled and were expected to hand in six stories over the year. By the end of the year, perhaps a dozen remained. I handed in 12 stories, as I recall, most of them crap; but they got better as I went on and in my final year, one was published in Saturday Night at the Forum, an anthology of new Quebec writers.

The point is that courses can nurture your talent and give you a safe environment in which to experiment and find your voice, make your mistakes and learn from them. Anyone hoping to write a book should test drive their material in a class or writing group.

Writing newscasts for CJAD radio in Montreal.

During my last year at Concordia, CJAD asked the faculty to recommend a student intern to help with election coverage. I was nominated and did well enough that they offered me a job writing news once a week, Saturday mornings. By the end of the school year, I was working six nights a week, six p.m. to midnight.

The experience was invaluable. I was told early on that people listening to radio news needed clear, direct writing because unlike newspaper readers, if they heard something they didn’t quite get, they couldn’t reread it. There’s no question it helped me forge a clean, active style that has served me well ever since.

Later that year, the Montreal Star offered me a summer internship as a crime reporter. Again, I had to focus my writing, keep it strong and uncluttered. At the end of the sumnmer, they hired me on full-time. Sadly, the paper folded in late September, a victim of a long strike that decimated its readership and a trend toward consolidation in the business. I never worked in mainstream media again

Working as a police reporter gave me my first taste of it. Reading the novels of Ross Macdonald showed me that crime novels could be more than “murder mysteries.”

Working as a police reporter gave me my first taste of it. Reading the novels of Ross Macdonald showed me that crime novels could be more than “murder mysteries.”

Like many other crime writers—including John Connolly, Linwood Barclay, Declan Hughes and others—I was inspired by the works of the late Ross Macdonald. Around the time I left school, I was helping my grandparents move from the house they had lived in for thirty odd years and came across one of his novels in the basement. I read the first few pages and was hooked. Unlike some of the modern writers of the day, Macdonald had the strong narrative voice I respected so much, and his explorations of family secrets and tensions resonated within me for reasons best told late at night over brimming glasses of Scotch.

I searched out all of his books and read and reread them, then moved to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler—whom I also read obsessively, and over the next 25 years, averaged at least one crime novel a week

It was four years from the day I scribbled my first notes to the time the final copy edit was complete.

It was four years from the day I scribbled my first notes to the time the final copy edit was complete.

I started the book that became Buffalo Jump in July 2003 at a cottage we rented on Georgian Bay. I scribbled a note on the back of an envelope that set out the initial premise: what if a hitman was given a job he couldn’t bring himself to do, and needed a detective to help him sort it out? For the next year, I did nothing but make notes until I had the character of Jonah Geller and the story arc firmly in my head. I started the first draft in July 2004 at the same cottage on the bay, and kept going for six months, often getting up at four or five in the morning to get in a few hours before the kids woke up (I was still working full-time in corporate communications).

In February of 2005, I signed with agent Helen Heller, who encouraged me to undertake significant revisions, which I did over the next fourteen months. Helen is a brilliant story editor, having worked in that capacity for 20 years before becoming an agent. When she thought the text was ready–spring of 2006–she sent it out to a number of publishers and we eventually got a two-book deal with Random House. Publisher Anne Collins then suggested some further revisions, which again took several months. It wasn’t until July of 2007 that the final edit was done–once again at the cottage on the bay.

About one year, give or take a few months.

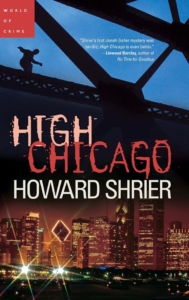

I started High Chicago as soon as Buffalo Jump went out to publishers. Got off to one false start: the original story line had to do with drug treatment and illegal methadone sales, because I wanted to draw on my experience as a writer for what was then known as the Addiction Research Foundation (now CAMH). But once I got into the swing of it, it took a little over a year.

Knowing the main characters (Jonah, Jenn, Dante Ryan) made a huge difference. I also made fewer mistakes the second time out. Niether my agent nor editor had very many changes to suggest to the manuscript, as compared to Buffalo Jump.

You can read more about that in this Globe and Mail essay

Write a good book and get an agent.

Publishing these days is a difficult business. Fewer titles are being accepted as publishers look for books that will be commercially successful–big hits, as it were. Publishers do not exist to make our literary dreams come true. Although most people I’ve met in the business are truly passionate about books and writers, they still have to make money. They know first books may not sell all that well, so they are looking for writers who have more than one book in them. In crime fiction, they are often looking for a series that will have legs. My publisher, the wonderful Anne Collins of Random House Canada, has told me many times that it may take three or four books to create enough momentum to launch my career. When I met Anne and Marion Garner, publisher of Vintage Canada, the first thing they said was how much they liked Buffalo Jump. The second thing was, “Do you have a second book going?”

Yes, but the odds are stacked against you.

Most publishers will read books submitted directly by authors–eventually. The problem is, they get many more than they can read in a timely fashion. Slush piles, as they are called, are huge at most houses, even the smaller ones. A large publisher like Random House gets dozens a week.

“Agented” manuscripts, on the other hand, are usually read quickly, especially if the agent is respected and has done business with the publisher before. My agent, Helen Heller, has a number of authors who are published by Random House, including Giles Blunt and Kelley Armstrong. So getting my manuscript in the door wasn’t as difficult as it might otherwise have been.

Research the agents who represent work like yours and submit a superior manuscript.

The story of how I got my agent is possibly the most instructive thing I can offer to aspiring writers.

After I attended Bouchercon (the world mystery writers conference) in Toronto in 2004, I became determined to find an agent. My manuscript was near completion and I felt it was good enough at that point to get published. (Little did I know how much work still lay ahead.)

I did some research first: asked other writers who represented them and consulted various web sites that listed agents in Toronto who represented crime writers. I narrowed my search down to three, including Helen Heller, and submitted query letters. None of them answered. I kept working on my manuscript, especially the first five chapters, which I thought would make a good sample, and which took the reader through to Jonah Geller’s first meeting with hit man Dante Ryan.

About two months later, in January 2005, I signed up for a one-day workshop at Humber College. Writers could submit the first page of their book, and it would be critiqued by the course instructor, Kim Moritsugu, the program director, Antanas Sileikas, and a guest from the industry, in this case the publisher of a mid-sized Canadian press. On that day, a Saturday, I woke up to one of the coldest days of the year, about 30 below. Did I really want to drag my butt out of bed and drive across the city in that weather for a 9 a.m. start? No. But I forced myself to do it and the rest, as they say, is history.

My page was well enough received that the publisher agreed afterward to read my sample. The sample was good enough that he responded within a day and asked to read the rest of the MS. At that point, I contacted Helen Heller again. Why Helen? She had a great reputation in the industry and she represented other crime writers, including Giles Blunt and Linwood Barclay. This time, in my letter, I mentioned that a publisher was interested in my book and she agreed to read the same five chapters. That same day, she called and asked for the rest of the book. After reading it she offered to represent me, if I was willing to undertake some substantial revisions.

The main things to take from this are:

1) Do your research. Make a list of agents who seem right for your work. There are plenty of resources that can help you, including the dedication pages of books where most authors thank their agents.

2) Polish your manuscript. You never know when your opportunity might come and you’ll want to be ready.

3) Make your own luck. Attend workshops, conferences and other events where you might meet agents or people who know them.

4) Be open to suggestion. I could easily have told Helen I didn’t want to rewrite my book. But I took her suggestions to heart and wound up with a far better book than I started with.

5) A pitch is not enough. You could tell an agent you have the greatest idea ever–the DaVinci Code meets Hannibal Lecter–and she’ll still say, Prove you can write it. Don’t try to get an agent and then write your MS.

6) Forget gimmicks. Most agents are not interested in pitches, balloon-o-grams, fancy packaging or anything else.

7) Think about the market. Like publishers, agents are in business to earn a living. Most charge 15% commission on your earnings. So to make a half decent living after paying expenses, an agent’s stable of authors have to bring in a fair amount of royalties.

8) Avoid shysters. If an agent askes you for any money upfront, do not walk–run in the opposite direction. Legitimate agents only charge commissions.

To forget the marketplace and write what’s in their heart.

I taught a writing course called Mystery and Suspense at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies this spring. If there is anything I tried to communicate above all else, it was this: forget what you think the marketplace wants. Serial killers or vampires or alcoholic, dysfunctional detectives might be all the rage these days, but a first book will likely take years to write and publish, by which time public tastes may well have changed. When I started Buffalo Jump, I never said to myself, “Gee, the market is really hot for a secular Jewish detective with a desire to perform acts of tikkun olam–repairing the world–to make up for things he did while in the Israeli army. That’s the story I had in me and that’s what I wrote. And that’s the advice I gave my students. Create a character only you can create, in a setting you can bring to life better than anyone else.

And just as important as the story you have is the voice in which you tell it. Will it be first-person? Third? One point of view or many? Will it be dark and brooding or light and funny? Again, each writer has to go with what works best for them.

I told my students to read mysteries. Read a ton. I read crime fiction of every type for twenty-five years before I attempted my first book. It certainly helped shape my views of what I liked and didn’t like in the field.

I told them to outline their work before they plunged into the text. Not every writer takes this approach. Peter Robinson told me that he does not outline; he just has his detectives find a body and lets them take it from there. This may work for police procedurals but not for private investigators, since they are rarely the first ones to discover a body; they are usually called in either when police are not wanted, as is the case in Buffalo Jump, or have been unable to provide closure to the victim’s family, as in High Chicago. Outlining helps you shape the story and avoid painting yourself into corners. And contrary to what some people say, it does not take anything away from the creative process. For me, it makes it richer. The ‘aha’ moments just come at a different time.

I told them books are made of good scenes, where characters collide and stakes are constantly raised. As in acting, obstacles bring out the best and worst in people.

I told them to research their subjects carefully. You don’t have to know everything about police procedure, forensics, criminal psychology and local flora and fauna to write a convincing mystery. But whatever you do include should be accurate. I’ve read manuscripts that had police investigators doing things no professional would do (failing to secure or search crime scenes, allowing bodies to be moved without the consent of a medical examiner). Whether your investigator is an amateur or a pro, know your setting, your jurisdiction and how things work there.

And finally I told them to look for stories that engaged them. Made them angry. Made them want to learn more. In Buffalo Jump, Jonah is furious at the thought that someone would target a mother and child for murder because of something the father did. In High Chicago, he’s enraged at the thought that real estate developers would put up a building on polluted land, and kill anyone who gets in their way.

There’s a lot more that was said in the eight weeks we were together, but that’s the gist of it: read a lot; write a lot; find what is unique in your own life, character, voice and story. Don’t worry about following trends. Aim to set new ones.

And never give up, as long as you have another good sentence in you.

At least one of the following: a Jewish author, protagonist, setting or world view

Cheryl Freedman, former executive director of the Crime Writers of Canada, recently asked me what makes a Jewish crime book Jewish, in preparation for a lecture she was giving. Here’s how I answered her five questions.

In general, what would you say makes a Jewish crime book Jewish? Would you consider your book(s) Jewish crime books?

I definitely consider both Buffalo Jump and High Chicago to be “Jewish” books. The author is Jewish, as is the protagonist. In Buffalo Jump, the family Jonah is trying to save is Jewish; so is the woman who hires him in High Chicago to explore her daughter’s apparent suicide. In Canadian film and TV, I am learning that a project is as Canadian as its creators and cast. So I think you have to have at the least, a Jewish author or a book about Jews, like Laura Lippman’s By a Spider’s Thread.

Is your world view essentially a Jewish one in your opinion?

I was raised in a small Jewish community (Chomedey) north of Montreal. I went to school in the basement of the shul. I went to Jewish camps and Bnai Brith. I barely knew any non-Jews until I got to CEGEP (Grade 12-13). Now I live a largely secular life–thank God I’m an atheist–but I send my kids to Jewish day school and we celebrate holidays and light Shabbat candles onFriday night and try to pay attention to tikkun olam. It’s all a massive contradiction. But my world view–like Jonah’s–cannot help be influenced by Judaism. It’s in the blood, the cultural memory, the collective experience and the immediate family.

What makes your book Jewish (apart from the fact that your protagonist has probably been circumcised and bar mitzvahed)?

What makes the books Jewish is Jonah’s point of view. As a first-person voice, everything comes through his lens, which is coloured as per answer 2.

Could you make your protagonist a gentile and still retain the flavour of the book or is the fact that he’s Jewish integral to the premise of the series?

4) I don’t think a non-Jewish hero would have a world view or voice like Jonah’s, and I doubt a non-Jewish writer could create a consistent Jewish hero like him.

Why did you make your protagonist Jewish?

Jews are in many ways the ultimate outsiders, excluded for hundreds of years from so many communities worldwide, shoved into ghettoes and shtetls, unable to own land or hold the same rights as other citizens. We are outsiders and have a two thousand year old tradition of commentary. When people ask why so many Jews made great comics, I point to this. We are observers of the larger world. We take note, we express ourselves with humour, regret, anger and wisdom. We are likelier to be sportswriters than athletes–observers, rather than participants.

I made the protagonist Jewish because I wanted to write a first-person private investigator story. It had been building in me since the seventies when I was a crime reporter for the Montreal Star and just discovering the novels of Ross Macdonald. And I wanted the hero to have my voice, my sense of humour, my view of the added joys and burdens of being born Jewish.

But finding the right protagonist to be my front man was by far the hardest part of writing my first book. Police work does not run in Jewish families the way it might in the Irish of New York and Boston. I’m no Robert Crais, who comes from a long line of police officers. I wanted my PI to be professional and realistic, but this is not something a nice Jewish boy from Toronto would ordinarily take up. Beyond the research I did, I had to search long and hard internally for the best part of a year until Jonah Geller finally appeared in his current incarnation. His stint in the Israeli army, the death of his father, the onset of atheism, his testy relationship with his brother, the expectations of his mother: these were all parts of the story I could uniquely tell and I think that’s a big part of what first-time authors should look for

I wish.

The full question from a reader: “Does your work ever come to you fully formed? I ask because a friend read a newspaper article and immediately imagined the voices of all three people in the article (first person in each case). The result was a best-selling novel and movie. I wonder if anything like that has happened for you, either for part of a novel or for the whole work?”

I only wish it did. My experience through three books has been that a general story line comes to me, gnaws at me, really. I do a lot of research and see what clings as I wade through the material. I rarely type in this phase. I make notes longhand, everything from snatches of dialogue to major shifts in story, and build an outline in three acts. When I feel charged enough to start a draft, I usually know most of the story. But never all.

Some characters have popped in fully formed. A good example is Andrew Cantor, the brother of Maya, whose apparent suicide leads Jonah into the case of High Chicago. I didn’t know she had a brother until he walked into the room, dark suit and all.

Dante Ryan is another who more or less stalked his way into my mind like the doorcrasher he is. Jonah Geller, on the other hand, took eight months to figure out.

Certainly no story has ever come to me in one go, not even in my stabs at short fiction